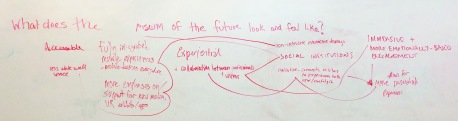

In our last class, our professor posed to our group the question we have been debating and wondering about all semester: What is the future of museums? What does the museum of the future look and feel like?

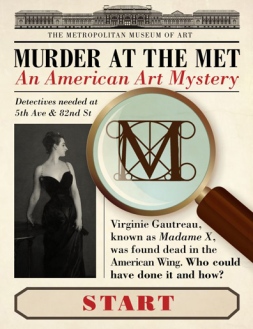

In class I contributed the following: that the museum of the future will become more experiential, by which I mean that museums will have to consider the sum experience of their audiences: what they see, how they can interact with each other and the museum collections, how they move through the space, and how they are engaged before and after their visits, to name a few arenas. To be more experiential, museums will need to become more engaging: they will need to engage all kinds of learners, engage all of our senses, engage all different ages, engage all kinds of visitors. To this point, I also proposed that museums will need to create ways that audiences can personalize their experience. Not all audience members have the same interests, learning types, attention spans, etc, so museums need to figure out how they can accommodate multiple kinds of visitors.

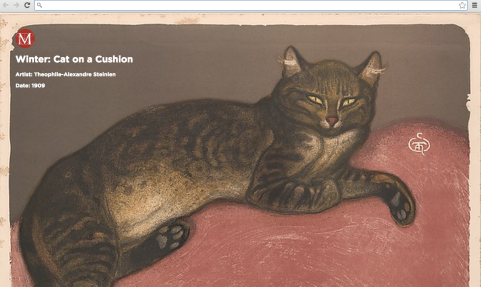

Technology will be a key tool to creating both of these kinds of experiences. I think in the future we will see more instances of tools that allow for engaging and personalized experiences. Some of these kinds of tools might include: the Cooper Hewitt Pen, the BLDG92 interactive timetable, Casa Batllo’s augmented reality video guide, and the American Museum of Natural History’s robot guides, to name a few of the examples I’ve discovered this semester. I imagine that most of these tools will continue to be supplemental experiences to the primary experience of interacting with and learning about the museum’s collection. While museums do want to stay up to date with these kinds of tools, I think some museums are realizing – like I experienced at the Whitney – that not all visitors want a technologically-innundated experience. Visitors will be given more choice in the kinds of experiences they can have.

I’ve really been thinking about this question a lot in the past week, especially as I read articles that attempt to answer this question (see my blog posts here and here). While I do still think museums of the future will be experiential and more personalized, I really don’t think there will be no one specific typology of the look and feel of museums of the future. Just like today we have some museums that experiment wildly with new technology, some that are a little more restrained, as well as some that completely eschew technology all together. In the future I think this will continue: some museums will continue to be very innovative and some will continue to provide an experience that is free of technological distraction. One thing I can be certain of: museums of the future will create experiences that look and feel wildly different. There are so many museums in the world that have different missions, collections, and educational goals and they will certainly not look or feel similarly.

However, in terms of the experience of visiting a museum: the two ideas I contributed both deal with the importance of the visitor and I do stand by the fact that visitor experience will be paramount in future museums. Many museums have or will come to realize that they must figure out what exactly their audiences want and they must accommodate them to stay relevant. Across all museums I think there will be an increase in professional interest in museum audiences: there will be more means of providing audience interaction, there will be more dedicated efforts to survey audience reaction, and there will be a more conscious effort to engage people, both in the physical museum space and through the museum’s online portals. Museums exist to educate – and they must remember who they are educating. Those audiences are they key to their continued existence, so museums of the future will have to pay close attention to what those audiences need.